Battle of Solferino

Battle of Solferino, (June 24, 1859), last engagement of the second War of Italian Independence. It was fought in Lombardy between an Austrian army and a Franco-Piedmontese army and resulted in the annexation of most of Lombardy by Sardinia-Piedmont, thus contributing to the unification of Italy.

After its defeat at the Battle of Magenta on June 4, the Austrian army of about 120,000 men had retreated eastward and Emperor Francis Joseph I had arrived to dismiss General Count Franz von Gyulai and take personal command. The Franco-Piedmontese army, of approximately equal size, under the command of Napoleon III of France and Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia-Piedmont, pursued the Austrians. Neither side had accurate information about the other’s troop movements, and on June 24 they unexpectedly clashed, in and around Solferino, four miles southeast of Castiglione delle Stiviere, in Lombardy, at a time when the French expected to engage only the Austrian rear guard and the Austrians expected to engage only the French advance units. The battle developed in a confused and piecemeal fashion until midday. After extremely costly fighting, the French broke the Austrian centre in midafternoon. Smaller actions, including a vigorous delaying action by the Austrian general Ludwig von Benedek, continued until dark, leaving the French and Piedmontese too exhausted to pursue the defeated Austrians. The Austrians lost 14,000 men killed and wounded and more than 8,000 missing or prisoners; the Franco-Piedmontese lost 15,000 killed and wounded and more than 2,000 missing or prisoners. These heavy casualties contributed to Napoleon III’s decision to seek the truce with Austria (see Villafranca, Conference of) that effectively ended the second War of Italian Independence. The bloodshed also inspired Henri Dunant to lead the movement to establish the International Red Cross.

Risorgimento

Italian history

Risorgimento, (Italian: “Rising Again”), 19th-century movement for Italian unification that culminated in the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861. The Risorgimento was an ideological and literary movement that helped to arouse the national consciousness of the Italian people, and it led to a series of political events that freed the Italian states from foreign domination and united them politically. Although the Risorgimento has attained the status of a national myth, its essential meaning remains a controversial question. The classic interpretation (expressed in the writings of the philosopher Benedetto Croce) sees the Risorgimento as the triumph of liberalism, but more recent views criticize it as an aristocratic and bourgeois revolution that failed to include the masses.

The main impetus to the Risorgimento came from reforms introduced by the French when they dominated Italy during the period of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1796–1815). A number of Italian states were briefly consolidated, first as republics and then as satellite states of the French empire, and, even more importantly, the Italian middle class grew in numbers and was allowed to participate in government.

After Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the Italian states were restored to their former rulers. Under the domination of Austria, these states took on a conservative character. Secret societies such as the Carbonari opposed this development in the 1820s and ’30s. The first avowedly republican and national group was Young Italy, founded by Giuseppe Mazzini in 1831. This society, which represented the democratic aspect of the Risorgimento, hoped to educate the Italian people to a sense of their nationhood and to encourage the masses to rise against the existing reactionary regimes. Other groups, such as the Neo-Guelfs, envisioned an Italian confederation headed by the pope; still others favoured unification under the house of Savoy, monarchs of the liberal northern Italian state of Piedmont-Sardinia.

After the failure of liberal and republican revolutions in 1848, leadership passed to Piedmont. With French help, the Piedmontese defeated the Austrians in 1859 and united most of Italy under their rule by 1861. The annexation of Venetia in 1866 and papal Rome in 1870 marked the final unification of Italy and hence the end of the Risorgimento.

Napoleon III

emperor of France

Napoleon III was the nephew of Napoleon I. He was president of the Second Republic of France from 1850 to 1852 and the emperor of France from 1852 to 1870. He gave his country two decades of prosperity under an authoritarian government but finally led it to defeat in the Franco-German War.

Napoleon III ruled France as emperor from 1852 to 1870. He was also president of the Second Republic from 1850 to 1852.

Napoleon III married countess Eugénie de Montijo in January 1853. She, later on, came to have a crucial influence on Napoleon III’s foreign policy.

Napoleon III (born April 20, 1808, Paris—died January 9, 1873, Chislehurst, Kent, England) was the nephew of Napoleon I, president of the Second Republic of France (1850–52), and then emperor of the French (1852–70). He gave his country two decades of prosperity under a stable, authoritarian government but finally led it to defeat in the Franco-German War (1870–71).

Youth in exile

He was the third son of Napoleon I’s brother Louis Bonaparte, who was king of Holland from 1806 to 1810, and his wife, Hortense de Beauharnais Bonaparte, stepdaughter of Napoleon I.

Louis-Napoléon’s childhood and youth were spent largely in exile. His mother, like all the Bonapartes, was banished from France in 1815 after the fall of Napoleon I. Eventually, she found a new home in Switzerland, where, in 1817, she bought the castle of Arenenberg. Of romantic disposition herself, she inspired young Louis-Napoléon with a longing for his lost fatherland, as well as with enthusiastic admiration of the genius of Napoleon I. After attending a grammar school at Augsburg, Germany (1821–23), her “sweet stubborn boy” was taught by private tutors. During visits to relatives in southern Germany and Italy, he became acquainted not only with other exiled victims of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy but also with the life of a suppressed people, such as those Italians who were living under Austrian and papal rule. He was, above all, interested in history and inspired by the idea of national liberty. Accordingly, he took part in an unsuccessful plot against the papal government in Rome in 1830 and in the rebellion in central Italy in 1831, in which his beloved brother perished. He himself was saved from the Austrian troops only by his mother’s bold intervention.

Claim to the throne

After the death in 1832 of his cousin the Duke of Reichstadt (Napoleon I’s only son), Louis-Napoléon considered himself his family’s claimant to the French throne. To be better prepared for his task, he completed his military training and pursued his studies of economic and social problems. Soon after, he felt ready to publish his own writings on political and military subjects. In his pamphlet “Rêveries politiques” (1832), he asserted that only an emperor could give France both glory and liberty. He thus wanted to make his name known, propagate his ideas, and recruit adherents. Convinced that as Napoleon’s nephew he would be popular with the French army, he vainly tried, on October 30, 1836, to win over the Strasbourg garrison for a coup d’état. King Louis-Philippe exiled him to the United States, from which he was recalled early in 1837 by his mother’s last illness. Expelled from Switzerland in 1838, he settled in England.

In 1839 he published “Des idées napoléoniennes.” So far, Bonapartism had been nothing but a wistful reminiscing of former beneficiaries of the empire or a romantic legend created by those who were dissatisfied with the humdrum present. In his new booklet Louis-Napoléon tried to transform Bonapartism into a political ideology. In doing so, he obeyed mystical inspirations as well as rationalism. To him, ideology and politics were the result of rational reflection as well as of belief. The central exponent in history was, in his opinion, the great personality called by Providence and representing progress. Napoleon I had been such a man, even though he was not allowed to finish his work. But Napoleon, the “Messiah of the new ideas,” was survived by the “Napoleonic idea,” for the “political creed,” like the religious creeds, had its martyrs and apostles. The Napoleonic idea was a “social and industrial one, humanitarian and encouraging trade,” that would “reconcile order and freedom, the rights of the people and the principles of authority.” Louis-Napoléon saw it as his task to accomplish this mission.

Landing with 56 followers, near Boulogne, France, on August 6, 1840, he was again unsuccessful. The town’s garrison did not join him. He was arrested, brought to trial, and sentenced to “permanent confinement in a fortress.” At his “university of Ham” (the castle in which he was held) he spent his time studying to fit himself for his imperial role. He corresponded with members of the French opposition and published articles in some of their newspapers. He also wrote several brochures, among them “Extinction du paupérisme” (1844), which won him some supporters on the left. It was not until May 25, 1846, that he succeeded in escaping and fleeing to Great Britain, where he waited for another chance to seize power.

Presidency

On hearing of the outbreak of the revolution, in February 1848, he travelled to Paris but was sent back by the provisional government. Some of his supporters, however, organized a small Bonapartist party and nominated him as their candidate for the Constituent Assembly. On June 4 he was elected in four départements but, awaiting more settled conditions, he refused to take his seat. Running again in September, he was elected in five départements, and after his arrival in Paris he lost no time in preparing to run for the presidency. He was supported by the newly founded Party of Order, which consisted of adherents of the Bourbons, Louis-Philippe, and Catholics. Lacking a suitable candidate, they regarded Louis-Napoléon—not a skilled parliamentarian but a popular figure—as a useful tool.

He used, now on a large scale, the kind of propaganda that had won him elections before. Because of his name and his descent, the Emperor’s nephew captivated the voters. Evoking the Napoleonic legend with its memories of national glory, Louis-Napoléon promised to bring back those days in time of peace. He succeeded also in recommending himself to every group of the population by promising to safeguard their particular interests. He promised “order” and “prosperity” to the middle class and the farmers and assistance to the poor. In December 1848 he was the only candidate to obtain votes—totalling 5,434,226—from among all classes of the population.

He took office, determined to free himself from dependence on the Party of Order, which had also won the parliamentary elections of May 1849. The government sent a military expedition to help the Pope reconquer Rome. At home it deprived active Republicans of their government positions and restricted their liberties, but the President could rely on only about a dozen members of the National Assembly who were Bonapartists. Prudently expanding his power by using every right the constitution granted him, Louis-Napoléon soon obtained key positions in the administration and in the army for his adherents. On October 31, he succeeded for the first time in appointing a Cabinet consisting of men depending more on him than on the National Assembly. By travelling through the country he gained wide popularity. Moreover, he used the disfranchisement of 3,000,000 electors of the poorer classes by the National Assembly in 1850 and an economic recession in 1851 as a pretext for agitating against the parties and for advertising himself as the “strong man” against the danger of a nonexistent revolution.

The constitution forbade the reelection of the president after expiration of his four-year term, and when Louis-Napoléon realized that he could not obtain the three-fourths majority necessary for a revision of the constitution he carried out a coup d’état on December 2. Only the Republicans dared to resist him. On December 4 they were defeated in street fighting in Paris, just as they were in other towns and in some regions. Arrests and deportations numbered in the thousands. Louis-Napoléon dissolved the Legislative Assembly and decreed a new constitution, which among other provisions restored universal suffrage. A plebiscite approved the new constitution. Encouraged by his success, he held another plebiscite in November 1852 and was confirmed as emperor after the resolution of the Senate concerning the restitution of the empire. Failing to obtain the hand of a princess of equal birth, Napoleon III married the countess Eugénie de Montijo in January 1853.

Domestic policy as emperor of Napoleon III

Napoleon III intended to be always ahead of public opinion so as to be able to understand the requirements of his time and to create laws and institutions accordingly. Hence, he took the greatest pains to study the public opinion and to influence it by means of propaganda. Although promising “reasonable freedom,” for the time being he considered it necessary to use the methods of a police state.

Willing “to take the initiative to do everything useful for the prosperity and the greatness of France,” he promoted public works, the construction of railroads, the establishment of institutions of credit, and other means of furthering industry and agriculture. An enthusiastic promoter of great technical projects, he supported inventors and took a personal interest in the rebuilding of modern Paris.

He did not, however, disavow what he called his “love of the diligent and needy.” He ensured a lower price for bread, furthered the construction of hygienic dwellings for workers, and established boards of arbitration. In his societies of mutual assistance, employers and employees were to learn to understand each other. He hoped that his social-welfare institutions, to the endowment of which he frequently contributed, would be imitated by the citizens. The middle class, however, looked upon him only as its protector against Socialism and regarded his social ideas as mere utopianism.

Foreign policy as emperor

Napoleon IIIPortrait of Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I.

As in domestic policy, the Emperor immediately took the initiative in foreign affairs. “Louis-Philippe fell because he let France fall into disrepute. I must do something,” he declared. He wanted to make France a great power once more by breaking up the European system created by the Congress of Vienna of 1815, which, incidentally, had imposed great humiliations on France. Convinced that in the present “epoch of civilization the successes of armies were only temporary” and that it was “public opinion which always gained the final victory,” he planned “to march at the head of generous and noble ideas,” among which the principle of nationality was the most important. In accordance with this principle he wanted an international congress to reconstruct “the European balance of power on more durable and just foundations.” And “if other countries gain anything France must gain something also.”

The Crimean War offered him a chance of realizing one of his favourite ideas: the conclusion of an alliance with Great Britain that would succeed in checking Russian expansion toward the Mediterranean. After the Paris conference, at which the peace terms were settled, Napoleon seemed to become Europe’s arbitrator. Ironically, it was an attempt on his life by Felice Orsini, an Italian revolutionary (January 1858), that reminded him of his wish “to do something for Italy.” Together with Piedmont-Sardinia, he went to war against Austria in order to expel it from Italy. A promoter of technical warfare, he witnessed the success of his modernized artillery and of the military use of the captive balloon. The fact that at the victorious Battle of Solferino in June 1859 he had been in command convinced him of his military genius. Yet, frightened by the possibility of intervention by the German Confederation, he suddenly made peace. Outmanoeuvred by Count Cavour, who confronted him with a unified Italy instead of the weak federation he had intended, he received Nice and Savoy as a reward. His activities in Italy displeased the British. Despite the conclusion of an Anglo-French commercial treaty in 1860, they remained suspicious and apprehensively watched his construction of armoured warships and his colonial and oriental policies.

Napoleon III dreamed of “opening new ways to commerce and new outlets to European products overseas,” of accelerating “the progress of Christianity and civilization.” He was therefore open to a colonial policy bent on furthering commercial interests and the establishment of bases. He intensified the extension of French power in Indochina and West Africa. In the Middle East the Emperor hoped that a better treatment of the Algerians would have a favourable influence on the Arabs from Tunisia to the Euphrates. He supported the construction of the Suez Canal. When the Roman Catholic Maronites who were under French protection in Lebanon were persecuted in 1860, he hoped to profit politically by dispatching an expeditionary force.

Attempts at reform of Napoleon III

In 1860 Napoleon III believed his regime to be stable enough to grant certain freedoms. The commercial treaty with Great Britain was to be the beginning of a new economic policy based on free-trade principles, with the aim of increasing prosperity and decreasing the cost of living. Dissatisfied with the functioning of the legislature, the Emperor decided to give “the great bodies of the state a more direct part in the formation of the general policy of our government.”

His hopes were not fulfilled to the extent he had expected. A deterioration in the economy caused dissatisfaction among the middle class and the working people, who joined the Catholics, angered by his anti-papal Italian policy, to become a steadily growing opposition. In the elections of 1857 only five members of the opposition had gained seats in the National Assembly; six years later there were 32.

At this very time, repeated bladder-stone attacks temporarily incapacitated the Emperor, who had been in poor health since 1856. He had always insisted on exercising control over all decisions of government; in his ministers he had seen nothing but tools. Now, he became dependent on persons in his entourage who formed groups and intrigued against each other. In 1863 the authoritarian Eugène Rouher, nicknamed the “Vice Emperor,” became prime minister; on the other hand, Napoleon III took the advice of his half brother the Duke of Morny to continue his policy of liberalization. With the help of his uncle Jérôme Bonaparte, who preached a democratic Bonapartism, he tried to win over the workers. But his concessions (freedom of coalition in 1864, freedom of assembly in 1868, extension of the rights of members of parliament, and liberalization of the press laws) were restricted by too many reservations and came too late. He allowed Victor Duruy, his minister of education from 1863, to fight clerical influence in education, yet on the other hand he tried to reconcile French Catholics by working for a compromise settlement in disputes between the papacy and the new Italian kingdom.

In 1861, by proposing to make the Austrian archduke Maximilian emperor of Mexico and by negotiating with the president of Ecuador about a projected “Kingdom of the Andes,” he had begun his Latin-American venture. He had expected material rewards for France and also hoped that the planned kingdom would check the growing influence of the United States in Latin America. Yet, as soon as the United States had concluded its Civil War it forced the French to withdraw. In Europe when the Polish insurrection broke out in 1863, he did not, in spite of his sympathy, dare to support Poland against Russia. Nevertheless, such sympathies led to an estrangement from Russia. Moreover, the great powers refused Napoleon’s proposal of a conference for the reorganization of Europe. Regarding Otto von Bismarck’s policy with a certain benevolence, he kept aloof when Prussia settled the Schleswig-Holstein question by a war on Denmark. He had always sympathized with Prussia and the idea of the extension of Prussia’s power in North Germany. He did not, however, openly tell Bismarck what price he demanded for his help. When in 1866, after routing Denmark, Prussia turned on its former ally, Austria, and defeated it more quickly than Napoleon had expected, he refused any armed intervention in its favour and only acted as mediator. Bismarck, however, was not willing to pay for Napoleon’s neutrality by the cession of German territories. The emperor’s plans to obtain compensation in Belgium failed, as did his attempt to gain Luxembourg in 1867. The retreat of Prussian troops from the fortress Luxemburg was no satisfactory reward: “Bismarck tried to cheat me. A French emperor cannot be cheated,” grumbled Napoleon III, not willing to allow the Prussians to cross the Main River line and extend their power into southern Germany, which was Bismarck’s obvious aim.

Last years

The emperor’s failures in foreign affairs strengthened the opposition. When in the 1869 elections the government received 4,438,000 votes against the opposition’s 3,355,000, Napoleon recognized that a genuine change of the regime was inevitable. In January 1870 he appointed Olivier-Émile Ollivier, whom Morny had recommended as the most appropriate prime minister for a liberal empire. The new Cabinet informed Great Britain and Prussia that France was ready to disarm, but Bismarck refused to cooperate.

On July 2 it became known that a Hohenzollern prince, a relative of the king of Prussia, was a candidate for the Spanish throne. In Paris this was regarded as Prussian interference in a French sphere of interest and a threat to security. Using his favourite means of secret diplomacy, Napoleon played a major part in causing the Hohenzollern prince to renounce his candidature. But then the sick emperor, influenced by the advocates of a belligerent policy, set out to humiliate Prussia by demanding that the candidature of the Hohenzollern prince would never be revived. As a result, war broke out on July 19. At the Battle of Sedan the sick emperor tried in vain to meet his death in the midst of his troops, but on September 2 he surrendered. He was deposed, and on September 4 the Third Republic was proclaimed.

Napoleon was released by the Germans and went to live in England. He studied technical and social problems, defended his politics in various publications, and even thought of landing in France to regain his throne. He died after undergoing an operation for the removal of bladder stones.

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, the Habsburg empire from the constitutional Compromise (Ausgleich) of 1867 between Austria and Hungary until the empire’s collapse in 1918. A brief treatment of the history of Austria-Hungary follows. For full treatment, see Austria: Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. The empire of Austria, as an official designation of the territories ruled by the Habsburg monarchy, dates to 1804, when Francis II, the last of the Holy Roman emperors, proclaimed himself emperor of Austria as Francis I. Two years later the Holy Roman Empire came to an end. After the fall of Napoleon (1814–15), Austria became once more the leader of the German states, but the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 resulted in the expulsion of Austria from the German Confederation and caused Emperor Franz Joseph to reorient his policy toward the east and to consolidate his heterogeneous empire. Even before the war, the necessity of coming to terms with the rebellious Hungarians had been recognized. The outcome of negotiations was the Ausgleich concluded on February 8, 1867.

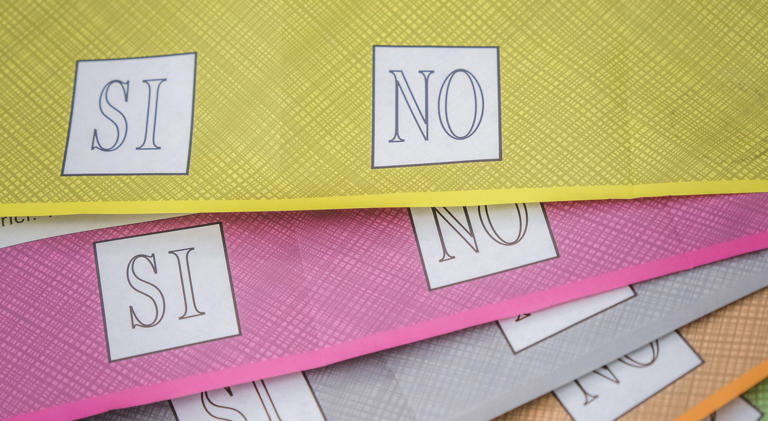

The agreement was a compromise between the emperor and Hungary, not between Hungary and the rest of the empire. Indeed, the peoples of the empire were not consulted, despite Franz Joseph’s earlier promise not to make further constitutional changes without the advice of the imperial parliament, the Reichsrat. Hungary received full internal autonomy, together with a responsible ministry, and, in return, agreed that the empire should still be a single great state for purposes of war and foreign affairs. Franz Joseph thus surrendered his domestic prerogatives in Hungary, including his protection of the non-Magyar peoples, in exchange for the maintenance of dynastic prestige abroad. The “common monarchy” consisted of the emperor and his court, the minister for foreign affairs, and the minister of war. There was no common prime minister (other than Franz Joseph himself) and no common cabinet. The common affairs were to be considered at the delegations, composed of representatives from the two parliaments. There was to be a customs union and a sharing of accounts, which was to be revised every 10 years. This decennial revision gave the Hungarians recurring opportunity to levy blackmail on the rest of the empire. The Ausgleich came into force when passed as a constitutional law by the Hungarian parliament in March 1867. The Reichsrat was only permitted to confirm the Ausgleich without amending it. In return for this, the German liberals, who composed its majority, received certain concessions: the rights of the individual were secured, and a genuinely impartial judiciary was created; freedom of belief and of education were guaranteed. The ministers, however, were still responsible to the emperor, not to a majority of the Reichsrat.

The official name of the state shaped by the Ausgleich was Austria-Hungary. The kingdom of Hungary had a name, a king, and a history of its own. The rest of the empire was a casual agglomeration without even a clear description. Technically, it was known as “the kingdoms and lands represented in the Reichsrat” or, more shortly, as “the other Imperial half.” The mistaken practice soon grew of describing this nameless unit as “Austria” or “Austria proper” or “the lesser Austria”—names all strictly incorrect until the title “empire of Austria” was restricted to “the other Imperial half” in 1915. These confusions had a simple cause: the empire of Austria with its various fragments was the dynastic possession of the house of Habsburg, not a state with any common consciousness or purpose.

International Committee of the Red Cross

International Committee of the Red Cross , international nongovernmental organization headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, that seeks to aid victims of war and to ensure the observance of humanitarian law by all parties in conflict. The work of the ICRC in both World Wars was recognized by the Nobel Prize for Peace in both 1917 and 1944. It shared another Nobel Peace Prize with the League of Red Cross Societies in 1963, the year of the 100th anniversary of the ICRC’s founding. The International Committee of the Red Cross was formed in response to the experiences of its founder, Jean-Henri Dunant, at the Battle of Solferino in 1859. Dunant witnessed thousands of wounded soldiers left to die for lack of adequate medical services. Soliciting help from neighbouring civilians, Dunant organized care for the soldiers. In 1862 he published an account of the situation at Solferino; by 1863 he had garnered so much support that the Geneva Society for Public Welfare helped found the International Committee for the Relief of the Wounded. In 1875 this organization became the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The ICRC is now one component of a large network including national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (The Red Crescent was adopted in lieu of the Red Cross in Muslim countries.) The governing body of the ICRC is the Committee, consisting of no more than 25 members. All the members are Swiss, in part due to the origins of the Red Cross in Geneva but also to establish neutrality so any countries in need can receive aid. The Committee meets in assembly 10 times each year to ensure that the ICRC fulfills its duties as the promoter of international humanitarian law and as the guardian of the Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross: “humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, voluntary service, unity, and universality.”

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi (born July 4, 1807, Nice, French Empire [now in France]—died June 2, 1882, Caprera, Italy) was an Italian patriot and soldier of the Risorgimento, a republican who, through his conquest of Sicily and Naples with his guerrilla Redshirts, contributed to the achievement of Italian unification under the royal house of Savoy. Early life

Garibaldi’s family was one of fishermen and coastal traders, and for more than 10 years he himself was a sailor. In 1832 he acquired a master’s certificate as a merchant captain. By 1833–34, when he served in the navy of the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, he had come under the influence of Giuseppe Mazzini, the great prophet of Italian nationalism, and the French socialist thinker the comte de Saint-Simon. Garibaldi, in 1834, took part in a mutiny intended to provoke a republican revolution in Piedmont, but the plot failed; he escaped to France and in his absence was condemned to death by a Genoese court.

Exile in South America

From 1836 to 1848, Garibaldi lived in South America as an exile, and these years of turmoil and revolution in that continent strongly influenced his career. He volunteered as a naval captain for the Rio Grande do Sul republic during that small state’s unsuccessful attempt to break free from the Brazilian Empire. Actually, he did little more than prey on Brazilian shipping. In the course of often harrowing adventures on land and sea, he managed to elope with Anna Maria Ribeiro da Silva (Anita), a married woman, who remained his companion in arms until her death. After a succession of victories by the Brazilians in 1839–40, Garibaldi finally decided to leave the service of Rio Grande. Driving a herd of cattle, he made the long trek to Montevideo with Anita and their son. There he tried his hand as commercial traveler and teacher but could not accustom himself to civilian life. In 1842 he was put in charge of the Uruguayan navy in another war of liberation—this time against Juan Manuel de Rosas, the dictator of Argentina. The following year, again in the service of Uruguay, Garibaldi took command of a newly formed Italian Legion at Montevideo, the first of the Redshirts, with whom his name became so closely associated. After he won a small but heroic engagement at the Battle of Sant’Antonio in 1846, his fame reached even to Europe, and in Italy a sword of honour, paid for by subscriptions, was donated to him.

He was in charge of the defense of Montevideo for a short time in 1847, when he first came to the attention of Alexandre Dumas père, who later did much to foster his reputation. Garibaldi also greatly impressed other foreign observers as an honest and able man. His South American experiences gave him invaluable training in the techniques of guerrilla warfare that he later used with great effect against French and Austrian armies, which had not been taught how to counter them. These first exploits in the cause of freedom cast him in the mold of a professional rebel, an indomitable individualist who all his life continued to wear the gaucho costume of the pampas and to act as if life were a perpetual battle for liberty.

War of liberation

In April 1848 Garibaldi led 60 members of his Italian Legion back to Italy to fight for the Risorgimento, or resurrection, of Italy in the war of independence against the Austrians. He first offered to fight for Pope Pius IX, then—when his offer was refused—for Charles Albert, the king of Piedmont-Sardinia. The king, too, rebuffed him, for Garibaldi’s conviction as a rebel in 1834 was still remembered; moreover, the regular army despised the self-taught guerrilla leader. Therefore, Garibaldi went to the aid of the city of Milan, where Mazzini had already arrived and had given the war of liberation a more republican and radical turn. Charles Albert, after his defeat at the hands of the Austrians at Custoza, agreed to an armistice, but Garibaldi continued in the name of Milan what had become his private war and emerged creditably from two engagements with the Austrians at Luino and Morazzone. But at the end of August, heavily outnumbered, he had to retreat across the frontier to Switzerland.

For a time Garibaldi settled down in Nice with Anita (whom he had married in 1842) and their three children, but his resolve to help free Italy from foreign rule was stronger than ever. He was confirmed in his purpose by his belief—which he and only a handful of others shared with Mazzini—that the many Italian states, though often engaged in internecine warfare, could nonetheless be unified into a single state. When Pius IX, threatened by liberal forces within the Papal States, fled from Rome toward the end of 1848, Garibaldi led a group of volunteers to that city. There, in February 1849, he was elected a deputy in the Roman Assembly, and it was he who proposed that Rome should become an independent republic. In April a French army arrived to restore papal government, and Garibaldi was the chief inspiration of a spirited defense that repulsed a French attack on the Janiculum Hill. In May he defeated a Neapolitan army outside Rome at Velletri, and in June he was the leading figure in the defense of Rome against a French siege. There was no chance at all of holding the city, but the gallantry of the resistance became one of the most inspiring stories of the Risorgimento. Refusing to accept defeat, Garibaldi led a few thousand men out of Rome and through central Italy in July 1849, maneuvering to avoid French and Austrian armies, until he reached the neutral republic of San Marino.

Retreat of Giuseppe Garibaldi

There Garibaldi found himself surrounded and decided to disband his men. Soon afterward, he was pursued by the Austrians as he tried to escape. Although Anita died, Garibaldi successfully crossed the Apennines to the Tuscan coast. The retreat through central Italy, coming after the defense of Rome, made Garibaldi a well-known figure. From then on he was the “hero of two worlds.” Some criticized his military skill in this campaign, but his qualities as a leader had proved to be extraordinary, and his courage and determination not to surrender were a lesson in patriotism for his fellow countrymen.

The Piedmontese monarchy, however, was too frightened to let this rebel return to his mother and children, and soon he was in exile again, first in Tangier, then on Staten Island, and finally in Peru, where he returned to his original trade as a ship’s captain. Only in 1854 was he allowed to return to Italy. The conte di Cavour, the prime minister of Piedmont, believed that by permitting Garibaldi’s repatriation he could pry him away from the republican Mazzini. In the following year, Garibaldi bought part of the island of Caprera off the Sardinian coast, which remained his home for the rest of his life. In 1856 he tried to lead an expedition to release political prisoners held by the Bourbon kings of Naples, but it came to nothing. In 1858 he received an invitation from Cavour to help prepare for another war against Austria. His task was to lead an army of volunteers from other Italian provinces, and he was given the rank of major general in the Piedmontese army. When war broke out in April 1859, he led his Cacciatori delle Alpi (Alpine Huntsmen) in the capture of Varese and Como and reached the frontier of the south Tirol. This war ended with the acquisition of Lombardy by Piedmont.

In September 1859, after peace had returned to northern Italy, Garibaldi transferred his attention to central Italy, where a revolutionary government had been established in Florence. There, on several occasions, he had private meetings with King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia, and it was agreed that he should prepare to invade the Papal States; the king would support his venture if it succeeded but disown him if it failed. At the last moment, however, the king realized that the undertaking was too dangerous and asked him to give up the idea. Garibaldi agreed, though reluctantly. He was ready at any moment to revive this kind of unwritten agreement with Victor Emmanuel, but it became increasingly clear that their aims were not identical. Though both men were patriots, Garibaldi was already working for the unification of Italy. The king was more prudent, concerned foremost with expanding Piedmont. Garibaldi was especially furious when, early in 1860, Cavour and Victor Emmanuel gave his hometown of Nice back to France (it had become Piedmontese in 1814), and he made one of his rare appearances in parliament to protest this violation of the national principle. In January 1860 he married Giuseppina, the daughter of the Marchese Raimondi, but abandoned her, within hours of the marriage, when he discovered she was five months pregnant, almost certainly by one of his own officers. Twenty years later, he was able to obtain the decree of nullity that enabled him to legitimize his children by Francesca Armosino, his longtime companion.

Conquest of Sicily and Naples

Giuseppe GaribaldiGiuseppe Garibaldi, 1860.

Giuseppe Garibaldi in SicilyGiuseppe Garibaldi with his 1,000 Redshirts landing at Marsala, Sicily, on May 11, 1860; etching.(more)

In May 1860 Garibaldi set out on the greatest venture of his life, the conquest of Sicily and Naples. This time he had no government backing, but Cavour and Victor Emmanuel did not dare to stop him, for he had become a popular hero. They stood ready to assist, but only if he proved successful, and he accepted this unwritten arrangement, confident that he could thus force Cavour to support a new move toward the unification of the Italian peninsula. Sailing from near Genoa on May 6 with about 1,000 men, he reached Marsala in Sicily on May 11 and in the name of Victor Emmanuel proclaimed himself dictator. A popular revolution in Sicily helped him considerably, for his personal charm was irresistible, and many of the peasants thought him a god intent on freeing them from slavery and feudalism. The decisive moment for his forces was a small engagement at Calatafimi, when he gave convincing proof that he could defeat the regular soldiers of the king of Naples’s army. Immediately there was a great popular movement in his support, and at the end of May he captured Palermo.

The seizure of Palermo was one of Garibaldi’s most remarkable military successes, and it convinced Cavour that this volunteer army should now be strongly, if still secretly, supported by Piedmont. Moving across the island, Garibaldi won the Battle of Milazzo in July, helped by reinforcements from northern Italy. In August he crossed over the Strait of Messina and landed on the mainland in Calabria. As always, his strategy was to deny the enemy a moment’s pause. After a lightning campaign, he moved up through Calabria and on September 7, 1860, entered Naples, Italy’s largest city, where he proclaimed himself “Dictator of the Two Sicilies” (the name of the territories of the king of Naples, comprising Sicily and most of southern Italy).

With 30,000 men under his command, he then fought the biggest battle of his career, on the Volturno River north of Naples. After his victory, he held plebiscites in Sicily and Naples, which allowed him to hand over the whole of southern Italy to King Victor Emmanuel. When the two met, Garibaldi was the first person to hail Victor Emmanuel as king of a united Italy. The king made a triumphal entry into Naples on November 7, and Garibaldi sat beside him in the royal carriage. But immediately afterward the former dictator returned to Caprera, refusing all the rewards thrust on him. He had asked for only one thing—to be allowed to continue governing Naples as the king’s viceroy until conditions returned to normal; but this was refused him, for in the eyes of the conservatives he was still a dangerous radical—an anticlerical who also professed to hold advanced ideas on social reform. He was also a man who was known to want to reconquer Rome from the pope and make it into Italy’s capital. This was too dangerous a scheme for Victor Emmanuel, for a French garrison defended papal temporal power in Rome. There was also another, more insidious danger: Garibaldi was more popular than the king himself. Furthermore, the regular army of Piedmont was deeply jealous of his successes and determined that he should not be permitted to score fresh ones. Finally, it was feared that Mazzini and the republicans might recapture Garibaldi’s allegiance and make him desert the monarchical cause.

Kingdom of Italy

Giuseppe GaribaldiGiuseppe Garibaldi, 1861.

In 1861 a new kingdom of Italy came into existence, but from the start it found Garibaldi virtually in opposition. Many people regarded him as an embarrassment. He opposed Cavour in parliament and accused the government of shabby treatment of the volunteer soldiers who had conquered half the country and given it to the king. Moreover, he condemned the inefficient administration of the provinces that he had conquered and for which he felt especially responsible. In many ways he showed that he considered himself almost an independent power, both in his dealings with his own government and with foreign powers. So admired abroad was Garibaldi that in July 1861 U.S. President Abraham Lincoln offered him a Union command in the American Civil War; the offer was declined, partly because Lincoln would not make a sweeping enough condemnation of slavery, but also because he would not give Garibaldi supreme command of the Federal troops. Another sign of Garibaldi’s reputation was the rapturous reception that he received in England in April 1864. Perhaps never before in history had there been such a large spontaneous gathering as the one that cheered him through the streets of London.

Last campaigns

Early in 1862 Victor Emmanuel again persuaded Garibaldi to lead a revolutionary expedition, this time to attack Austria in the Balkans. He was allowed to recruit another volunteer army, and munitions were collected for him in Sicily; but he then decided to use this army to attack the Papal States. Not wanting to jeopardize its relations with the French, the Italian government ordered its own forces to stop Garibaldi. At the ensuing Battle of Aspromonte, he was badly wounded and taken prisoner. When he was freed, however, the king’s complicity could no longer be denied. Garibaldi’s wound left him lame, but this did not prevent the government from using him more openly when war broke out with Austria in 1866. He was given an almost independent command in the Tirol, and once again he emerged from the war with a good deal more credit than any of the regular soldiers. This conflict led to the acquisition of Venice. In 1867 Garibaldi led another private expedition into the Papal States. This, too, was secretly subsidized by the government, though, of course, the king pretended otherwise; but political mismanagement of the whole incident forced France to intervene, and French troops defeated Garibaldi’s volunteers at Mentana. Once more he was arrested by the Italian government to cover up its complicity, but he was soon released and taken back to Caprera. Garibaldi led one final campaign in 1870–71, when he assisted the French Republic against Prussia. Again he distinguished himself, though on a small scale, and he was subsequently elected a member of the French National Assembly at Bordeaux.

During the last decade of his life he was crippled by rheumatism and by his many wounds. Though he had become something of a recluse on his island, he kept abreast of affairs through the numerous deputations that called on him, and he habitually made pronouncements on affairs of the day. Toward the end he called himself a socialist, but both Karl Marx and the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin disowned him. He also became something of a pacifist, for his own experience had taught him that wars were seldom either righteous or effective in achieving their ends. Garibaldi was recognized as a champion of the rights of labour and of women’s emancipation. Moreover, he showed himself to be a religious freethinker and ahead of his time in believing in racial equality and the abolition of capital punishment.

Legacy

One of the great masters of guerrilla warfare, Garibaldi was responsible for most of the military victories of the Risorgimento. Almost equally important was his contribution as a propagandist to the unification of Italy. A man of the people, he knew far better than Cavour or Mazzini how to reach the masses with the new message of patriotism. Furthermore, his use of his military and political gifts for liberal or nationalist causes coincided well with current fashion and brought him great acclaim. In addition, he attracted support by being a truly honest man who asked little for himself.

But Garibaldi’s forthright innocence coloured his politics. Not interested in power for himself, he nevertheless believed in dictatorship as a result of his South American experiences. He distrusted parliaments because he saw them to be ineffective and corrupt. Actually, his own dictatorship of southern Italy in 1860, though much criticized, compares surprisingly well with the subsequent administration by the Kingdom of Italy. There was little of the intellectual about Garibaldi, yet his simple radicalism sparked the first political awareness in many of his fellow countrymen and brought home to them the significance of nationality. Notwithstanding his turn toward socialism, he remained primarily a nationalist—but the object of his nationalism was always the liberation of peoples and not patriotic aggrandizement. To his embodiment of this aim he owes his eminent place in Italian history.

Red Cross and Red Crescent

Red Cross and Red Crescent, humanitarian agency with national affiliates in almost every country in the world. The Red Cross movement began with the founding of the International Committee for the Relief of the Wounded (now the International Committee of the Red Cross) in 1863. It was established to care for victims of battle in time of war, but later national Red Cross societies were created to aid in the prevention and relief of human suffering generally. Its peacetime activities include first aid, accident prevention, water safety, training of nurses’ aids and mothers’ assistants, and maintenance of maternal and child welfare centres and medical clinics, blood banks, and numerous other services. The Red Cross is the name used in countries under nominally Christian sponsorship, while Red Crescent (adopted on the insistence of the Ottoman Empire in 1906) is the name used in Muslim countries. The Red Cross arose out of the work of Henri Dunant, a Swiss humanitarian, who, at the Battle of Solferino, in June 1859, organized emergency aid services for Austrian and French wounded. In his book Un Souvenir de Solferino (1862; A Memory of Solferino) he proposed the formation in all countries of voluntary relief societies, and in 1863 the International Committee for the Relief of the Wounded was created. This organization in turn spawned national Red Cross societies.

The Geneva Convention of August 22, 1864, the first multilateral agreement on the Red Cross, committed signatory governments to care for the wounded of war, whether enemy or friend. Later, this convention was revised, and new conventions were adopted to protect victims of warfare at sea (1907), prisoners of war (1929), and civilians in time of war (1949). The worldwide structure of the Red Cross and Red Crescent now consists of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; Comité International de la Croix-Rouge); the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Fédération Internationale des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge); and the national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies. The governing committee of the ICRC is an independent council of 25 Swiss citizens with headquarters at Geneva. During wartime the ICRC acts as an intermediary among belligerents and also among national Red Cross societies. It also visits prisoners in war camps and provides relief supplies, mail, and information for their relatives. The ICRC was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1917 and 1944 and shared a third Nobel Prize for Peace with the League of Red Cross Societies (now International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) in 1963. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, which has a secretariat in Geneva, helps provide relief after natural disaster and aids in the development of national societies.

strategy

military

strategy, in warfare, the science or art of employing all the military, economic, political, and other resources of a country to achieve the objects of war. Fundamentals

Roman war galleyA Roman war galley with infantry on deck; in the Vatican Museums.

The term strategy derives from the Greek strategos, an elected general in ancient Athens. The strategoi were mainly military leaders with combined political and military authority, which is the essence of strategy. Because strategy is about the relationship between means and ends, the term has applications well beyond war: it has been used with reference to business, the theory of games, and political campaigning, among other activities. It remains rooted, however, in war, and it is in the field of armed conflict that strategy assumes its most complex forms.

Theoreticians distinguish three types of military activity: (1) tactics, or techniques for employing forces in an engagement (e.g., seizing a hill, sinking a ship, or attacking a target from the air), (2) operations, or the use of engagements in parallel or in sequence for larger purposes, which is sometimes called campaign planning, and (3) strategy, or the broad comprehensive harmonizing of operations with political purposes. Sometimes a fourth type is cited, known as grand strategy, which encompasses the coordination of all state policy, including economic and diplomatic tools of statecraft, to pursue some national or coalitional ends.

Strategic planning is rarely confined to a single strategist. In modern times, planning reflects the contributions of committees and working groups, and even in ancient times the war council was a perennial resort of anxious commanders. For example, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War (c. 404 bce) contains marvelous renditions of speeches in which the leaders of different states attempt to persuade their listeners to follow a given course of action. Furthermore, strategy invariably rests on assumptions of many kinds—about what is lawful or moral, about what technology can achieve, about conditions of weather and geography—that are unstated or even subconscious. For these reasons, strategy in war differs greatly from strategy in a game such as chess. War is collective; strategy rarely emerges from a single conscious decision as opposed to many smaller decisions; and war is, above all, a deeply uncertain endeavour dominated by unanticipated events and by assumptions that all too frequently prove false.

Carl von ClausewitzMilitary strategist Carl von Clausewitz, lithograph by Franz Michelis after an oil painting by Wilhelm Wach, 1830.

Such, at least, has been primarily the view articulated by the greatest of all Western military theoreticians, the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz. In his classic strategic treatise, On War (1832), Clausewitz emphasizes the uncertainty under which all generals and statesmen labour (known as the “fog of war”) and the tendency for any plan, no matter how simple, to go awry (known as “friction”). Periodically, to be sure, there have been geniuses who could steer a war from beginning to end, but in most cases wars have been shaped by committees. And, as Clausewitz says in an introductory note to On War, “When it is not a question of acting oneself but of persuading others in discussion, the need is for clear ideas and the ability to show their connection with each other”—hence the discipline of strategic thought.

Clausewitz’s central and most famous observation is that “war is a continuation of politics by other means.” Of course war is produced by politics, though in common parlance war is typically ascribed to mindless evil, the wrath of God, or mere accident, rather than being a continuation of rational diplomacy. Moreover, Clausewitz’s view of war is far more radical than a superficial reading of his dictum might suggest. If war is not a “mere act of policy” but “a true political instrument,” political considerations may pervade all of war. If this is the case, then strategy, understood as the use of military means for political ends, expands to cover many fields. A seeming cliché is in fact a radical statement.

There have been other views, of course. In The Art of War, often attributed to Sunzi (5th century bce) but most likely composed early in China’s Warring States period (475–221 bce), war is treated as a serious means to serious ends, in which it is understood that shrewd strategists might target not an enemy’s forces but intangible objects—the foremost of these being the opponent’s strategy. Though this agrees with Clausewitz’s ideas, The Art of War takes a very different line of argument in other respects. Having much greater confidence in the ability of a wise general to know himself and his enemy, The Art of War relies more heavily on the virtuosity of an adroit commander in the field, who may, and indeed should, disregard a ruler’s commands in order to achieve war’s object. Where On War asserts that talent for high command differs fundamentally from military leadership at lower levels, The Art of War does not seem to distinguish between operational and tactical ability; where On War accepts battle as the chief means of war and extensive loss of human life as its inevitable price, The Art of War considers the former largely avoidable (“the expert in using the military subdues the enemy’s forces without going to battle”) and the latter proof of poor generalship; where On War doubts that political and military leaders will ever have enough information upon which to base sound decisions, The Art of War begins and concludes with a study of intelligence collection and assessment.

To some extent, these approaches to strategy reflect cultural differences. Clausewitz is a product of a combination of the Enlightenment and early Romanticism; The Art of War’s roots in Daoism are no less deep. Historical circumstances explain some of the differences as well. Clausewitz laboured under the impact of 20 years of war that followed the French Revolution and the extraordinary personality of Napoleon; The Art of War was written during the turmoil of the Warring States period. There also are deeper differences in thinking about strategy that transcend time and place. In particular, differences in contemporary discussions of strategy persist between optimists, who think that the wisely instructed strategist has a better than even chance (other things being equal) to control his fate, and pessimists (such as Clausewitz), who believe that error, muddle, and uncertainty are the norm in war and therefore that chance plays a more substantial role. In addition, social scientists, exploring such topics as inadvertent war or escalation, have been driven by the hope of making strategy a rational and predictable endeavour. Historians, by and large, side with the pessimists: in the words of British historian Michael Howard, one of the best military historians of the 20th century, most armies get it wrong at the beginning of a war.

Strategy in antiquity

The ancient world offers the student of strategy a rich field for inquiry. Indeed, the budding strategist is probably best advised to begin with Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War (c. 404 bce), which describes the contest between two coalitions of Greek city-states between 431 and 404 bce. Athens, a predominantly maritime power, led the former members of the Delian League (now incorporated in the Athenian empire) against the Peloponnesian League, which was led by Sparta, a cautious land power. In the opening speeches rendered by Thucydides, the two leaders, Pericles of Athens and Archidamus II of Sparta, wrestle with strategic issues of transcendent interest: How shall they bring their strengths to bear on their enemy’s weakness, particularly given the different forms of power in which the two coalitions excel? How will the nature of the two regimes—the volatility and enterprising spirit of democratic Athens, the conservatism and caution of slaveholding Sparta—shape the contest?

From his study of the Peloponnesian War, the 19th-century German military historian Hans Delbrück drew a fundamental distinction between strategies based on overthrow of the opponent and those aimed at his exhaustion. Both Sparta and Athens pursued the latter; the former was simply unavailable, given their fundamental differences as military powers. Delbrück’s analysis illustrates the ways in which strategic concepts can transcend history. Suitably modified, they illuminate the choices made, for example, by Israel and its Arab enemies in the 1960s and ’70s just as well as they do those made by the ancient Greeks.

Alexander the Great’s empireAlexander the Great’s conquests spread Greek civilization and culture into Asia and Egypt. His vast empire stretched eastward into India.(more)

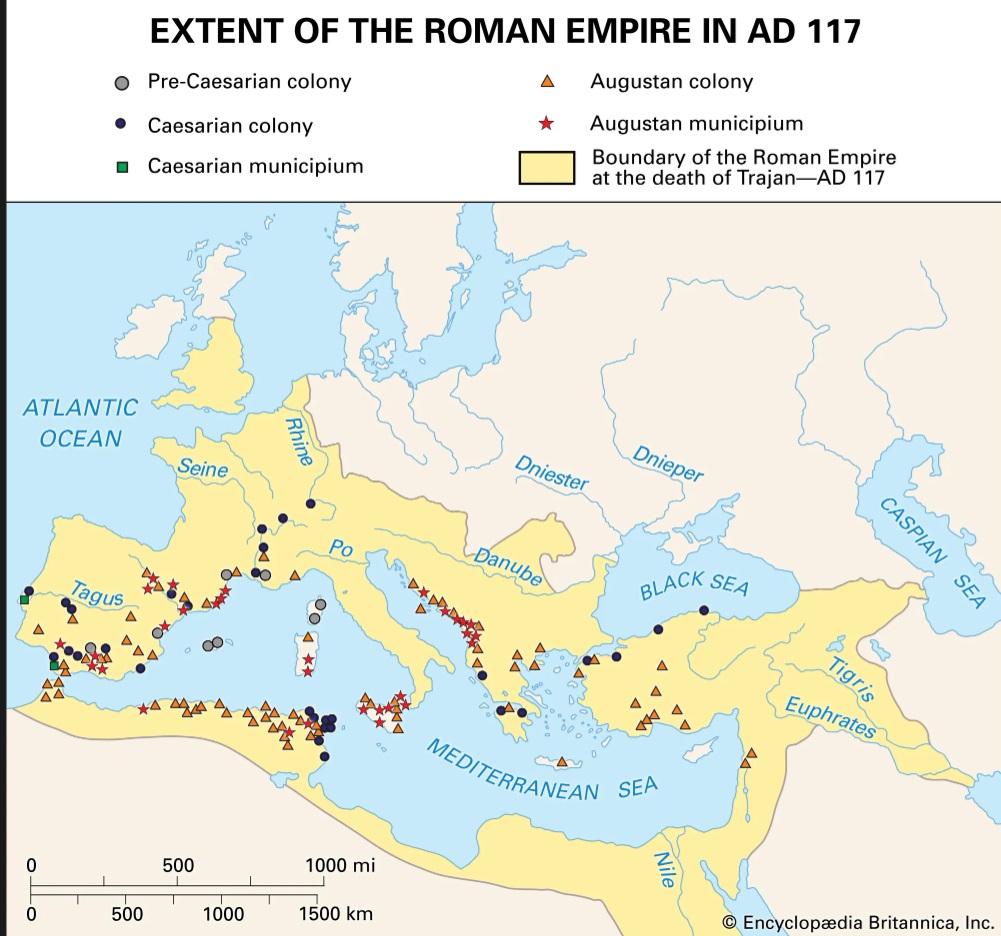

Ancient Greece is a story of distinctive states and eminent leaders, such as Alexander the Great, whose triumphs against the Persian empire in the 4th century bce illustrate the success of strategies of overthrow against centralized states unable to recuperate from a severe setback. The rise of ancient Rome, on the other hand, is far more a story of institutions. From the Greek historian Polybius in the 2nd century bce to the Florentine political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli in the 15th–16th century, the story of Roman strategy seems one of a collective approach to war rather than a reflection of the choices of a single statesman. Rome’s great strength, the ancient historians argue (and modern historians seem to agree), stemmed from political institutions that turned internal divisions into an engine of external expansion, that allowed for popular participation and executive decision, and that concentrated strategic decision making in a powerful Senate composed of the leading men of Rome. To its unique political constitution was added the Roman legion, a form of military organization far more flexible and disciplined than anything the world had yet seen—a fabulous tool for conquest and, in its attention to detail, from the initial selection of soldiers to their construction of camps to their rotation on the battle line, a model imitated in succeeding centuries.

Rome’s conquest of the Mediterranean world illustrates the idea of a tacit or embedded strategy. Rome’s ruthlessness in dividing its enemies, in creating patron-client relationships that would guarantee its intervention in more civil wars, its cleverness in siding with rebels or dissidents in foreign states, and its relentlessness in pursuing to annihilation its most serious enemies showed remarkable continuity throughout the republic.

The Second Punic War (218–201 bce) illustrates these propositions well. There were only two leading figures of note in Rome throughout the war: Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (Cunctator), who delayed and bought time while Rome recovered from its initial disastrous defeats, and Scipio Africanus the Elder, who delivered the final blow of the Second Punic War to Carthage at the Battle of Zama (202 bce). It does not appear that either was the equal of Hannibal, the brilliant Carthaginian general who administered defeat after defeat to superior Roman armies on their home turf. More important than personalities, however, was Rome’s unflinching determination to pursue its enemies, quite literally to the death. Hannibal was cornered in the Bithynian village of Libyssa and committed suicide, following a demand from Rome that he be turned over by Antiochus III of Syria, whom he had aided in rebellion against Rome following the defeat of Carthage. And Carthage itself—long the target of the grim senator Marcus Porcius Cato’s insistence that it be destroyed (he famously took to ending every oration with the words “Ceterum censeo delendam esse Carthaginem,” which translate as “Besides which, my opinion is that Carthage must be destroyed”)—was wiped out of existence in the Third Punic War (149–146 bce), which was provoked by Rome for the purpose of finishing off its most dangerous potential opponent.

Medieval strategy

Halberd and pikeHalberd and pike in battle near Ins, Berne canton, in 1375. Encumbered by heavy armor, the mounted French and English mercenaries are cut down by disciplined Swiss infantrymen wielding long armor-piercing weapons. Illustration from the Amtliche Chronik by Diebold Schilling, 15th century.(more)

Most military histories skim over the Middle Ages, incorrectly believing it to be a period in which strategy was displaced by a combination of banditry and religious fanaticism. Certainly, the sources for medieval strategic thought lack the literary appeal of the classic histories of ancient Greece and Rome. Nevertheless, Europe’s medieval period may be of especial relevance to the 21st century. In the Middle Ages there existed a wide variety of entities—from empires to embryonic states to independent cities to monastic orders and more—that brought different forms of military power to bear in pursuit of various aims. Unlike the power structures in the 18th and 19th centuries, military organizations, equipment, and techniques varied widely in the medieval period: the pikemen of Swiss villages were quite different from the mounted chivalry of western Europe, who in turn had little in common with the light cavalry of the Arabian heartland. The strategic predicament of the Byzantine Empire—beset by enemies that ranged from the highly civilized Persian and Arab empires to marauding barbarians—required, and elicited, a complex strategic response, including a notable example of dependence on high technology. Greek fire, a liquid incendiary agent, enabled the embattled Byzantine Empire to beat off attacking fleets and preserve its existence until the early 15th century.

In Delbrück’s parlance, medieval warfare demonstrated both types of strategy—overthrow and exhaustion. The Crusader states of the Middle East were gradually exhausted and overwhelmed by constant raiding warfare and the weight of numbers. On the other hand, one or two decisive battles, most notably the ruinous disaster at the Battle of Ḥaṭṭīn (1187), doomed the Crusader kingdom of Jerusalem, and earlier the Battle of Manzikert (1071) was a blow from which the Byzantine Empire never recovered fully.

the CitéMedieval fortifications of the Cité, Carcassonne, France.

Medieval strategists made use of many forms of warfare, including set-piece battles, of course, as well as the petty warfare of raiding and harassment. But they also improved a third type of warfare—the siege, or, more properly, poliorcetics, the art of both fortification and siege warfare. Castles and fortified cities could eventually succumb to starvation or to an assault using battering rams, catapults, and mining (also known as sapping, a process in which tunnels are dug beneath fortification walls preparatory to using fire or explosives to collapse the structure), but progress in siege warfare was almost always slow and painful. On the whole, it was substantially easier to defend a fortified position than to attack one, and even a small force could achieve a disproportionate military advantage by occupying a defensible place. These facts, combined with the primitive public-health practices of many medieval armies, the poor condition of road networks, and the poverty of an agricultural system that did not generate much of a surplus upon which armies could feed, meant limits on the tempo of war and in some measure on its decisiveness as well—at least in Europe.

Mongol Empire: mapMongol Empire.

The story was different in East and Central Asia, particularly in China, where the mobility and discipline of Mongol armies (to take only the most notable example) and the relatively open terrain allowed for the making and breaking not only of states but of societies by mobile cavalry armies bent on conquest and pillage. Strategy emerged in the contest for domestic political leadership (as in Oda Nobunaga’s unification of much of Japan during the 16th century) and in attempts either to limit the irruptions of warlike nomads into civilized and cultivated areas or to expand imperial power (as in the rise of China’s Qing dynasty in the 17th century). However, after the closure of Japan to the world at the end of the 16th century and the weakening of the Qing dynasty in the 19th century, strategy became more a matter of policing and imperial preservation than of interstate struggle among comparable powers. It was in Europe that a competitive state system, fueled by religious and dynastic tensions and making use of developing civilian and military technologies, gave birth to strategy as it is known today.

Strategy in the early modern period

Cardinal de RichelieuCardinal de Richelieu, detail of a portrait by Philippe de Champaigne; in the Louvre, Paris.

The development of state structures, particularly in western Europe, during the 16th and 17th centuries gave birth to strategy in its modern form. “War makes the state, and the state makes war,” in the words of American historian Charles Tilly. The development of centralized bureaucracies and, in parallel, the taming of independent aristocratic classes yielded ever more powerful armies and navies. As the system of statecraft gradually became secularized—witness the careful policy pursued by France under the great cardinal Armand-Jean du Plessis, duc de Richelieu, chief minister to King Louis XIII from 1624 to 1642, who was willing to persecute Protestants at home while supporting Protestant powers abroad—so too did strategy become more subtle. The rapine and massacre of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) yielded to wars waged for raison d’état, to aggrandize the interests of the ruler and through him the state. In this as in many other ways, the early modern period witnessed a return to Classical roots. Even as drill masters studied ancient Roman textbooks to recover the discipline that made the legions formidable instruments of policy, so too did strategists return to a Classical world in which the logic of foreign policy shaped the conduct of war.

For a time, the invention of gunpowder and the development of the newly centralized state seemed to shatter the dominance of defenses: medieval castles could not withstand the battering of late 15th- or early 16th-century artillery. But the invention of carefully designed geometric fortifications (known as the trace italienne) restored much of the balance. A well-fortified city was once again a powerful obstacle to movement, one that would require a great deal of time and trouble to reduce. The construction of belts of fortified cities along a country’s frontier was the keynote of strategists’ peacetime conceptions.

Yet there was a difference. Poliorcetics was no longer a haphazard art practiced with greater or lesser virtuosic skill but increasingly a science in which engineering and geometry played a central role; cities fell not to starvation but to methodical bombardment, mining, and, if necessary, assault. Indeed, by the middle of the 18th century, most sieges were highly predictable and even ritualized affairs, culminating in surrender before the final desperate attack. Armies also began to acquire the rudiments, at least, of modern logistical and health systems; though they were not quite composed of interchangeable units, they at least comprised a far more homogeneous and disciplined set of suborganizations than they had since Roman times. And, in a set of developments rarely noticed by military historians, the development of ancillary sciences, such as the construction of roads and highways and cartography, made the movement of military organizations not only easier but more predictable than ever before.

Strategy began to seem more like technique than art, science rather than craft. Practitioners, such as the 17th-century French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban and the 18th-century French general and military historian Henri, baron de Jomini, began to make of war an affair of rules, principles, and even laws. Not surprisingly, these developments coincided with the emergence of military schools and an increasingly scientific and reforming bent—artillerists studied trigonometry, and officers studied military engineering. Military literature flourished: Essai général de tactique (1772), by Jacques Antoine Hippolyte, comte de Guibert, was but one of a number of thoughtful texts that systematized military thought, although Guibert (unusual for writers of his time) had inklings of larger changes in war lying ahead. War had become a profession, to be mastered by dint of application and intellectual, as well as physical, labour.

The French Revolution and the emergence of modern strategies

The eruption of the French Revolution in 1789 delivered a blow to the emerging rationalistic conception of strategy from which it never quite recovered, though some of its precepts were echoed by later schools of thought, such as those of Jomini in his great work The Art of War (1838) and the systems analysts of the 1960s and afterward. The techniques of the armies of France under the Revolutionary government and later the Directory (1795–99) and Napoleon (1799–1814/15) were, superficially, those of the ancien régime: drill manuals and artillery technique drew heavily on concepts outlined in the days of Louis XVI, the last pre-Revolutionary French king. But the energy unleashed by revolutionary passion, the resources unlocked by mass conscription and a powerful state, and the fervour that followed from ideological zeal transformed strategy.

The author who understood this best was the Prussian Carl von Clausewitz, whose military experience spanned the years from 1793 to 1815, a period in which Europe was convulsed by a series of wars centring on France. The Prussian general’s masterpiece On War (1832) appeared shortly after his death. It described an approach to strategy that would, with modifications, last at least through the middle of the 20th century.

As noted in the section Fundamentals, Clausewitz combined Enlightenment rationalism with a deep appreciation of the turbulent and uncontrollable forces unleashed by the new era. For him, strategy was always the product of tension between three poles: (1) the government, which seeks to use war rationally as an instrument of policy, (2) the military, and in particular its commanders, whose skill and abilities reflect the unquantifiable element of creativity, and (3) the people, whose animus and determination are only partly subject to the control of the state. Thus, strategy is at once a matter of calculation and of instinct, a product of deliberation and purpose on the one hand and of emotion, uncertainty, and interaction on the other.

American Civil War: Union soldiers in trenchesUnion soldiers in trenches, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1863.

The wars of the mid-19th century, in particular the wars of German unification (Prussia’s wars with Denmark, Austria, and France in 1864, 1866, and 1870–71, respectively) and the American Civil War (1861–65), marked a peak of Clausewitzian strategy. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and U.S. Pres. Abraham Lincoln successfully waged war for great stakes. Exemplary Clausewitzian leaders, they used the new instruments of the time—the mass army, now sustained year-round by early industrial economies that could ship vast quantities of matériel to distant fronts—to achieve their purposes.

Yet, even in their successes, changes were already beginning to threaten the very possibility of Clausewitzian strategy. Mass mobilization produced two effects: a level of societal engagement that made moderation and compromise in peacemaking difficult and conscripted armies that were becoming difficult to handle in the field. “Very large assemblies of units are in and of themselves a catastrophe,” declared Prussian Gen. Helmuth von Moltke in his “Instructions for Large Unit Commanders” (1869). Furthermore, as military organizations became more sophisticated and detached from society, tension between political leaders and senior commanders grew. The advent of the telegraph compounded this latter development; a prime minister or president could now communicate swiftly with his generals, and newspaper correspondents could no less quickly with their home offices. Public opinion was more directly engaged in warfare than ever before, and generals found themselves making decisions with half a mind to the press coverage that was being read by an expanding audience of literate citizens. And, of course, politicians paid no less heed to a public that was intensely engaged in political debates. These developments portended a challenge for strategy. War had never quite been the lancet in the hands of a diplomatic surgeon; it was now, however, more like a great bludgeon, wielded with the greatest difficulty by statesmen who found others plucking at their grip.

T.E. Lawrence on guerrilla warfare: Strategy and tactics

HMS Inflexible; battleshipHMS Inflexible, a “central citadel” battleship of the Royal Navy. Launched in 1876, it mounted four 80-ton, 16-inch muzzle-loading guns in two hydraulically powered turrets. For greater stability, the engines and powder magazines were gathered toward the centre of the ship and protected by up to 24 inches of iron. The masts were removed in the 1880s.(more)

Compounding these challenges was the advent of technology as an important and distinct element in war. The 18th century had experienced great stability in the tools of war, on both land and sea. The musket of the early 18th century did not differ materially from the firearm carried into battle by one of the duke of Wellington’s British soldiers 100 years later; similarly, British Adm. Horatio Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) had decades of service behind it before that great contest. But by the mid-19th century this had changed. On land the advent of the rifle—modified and improved by the development of breech loading, metal cartridges, and later smokeless gunpowder—was accompanied as well by advances in artillery and even early types of machine guns. At sea changes were even more dramatic: steam replaced sail, and iron and steel replaced wood and canvas. Obsolescence now occurred within years, not decades, and technological experts assumed new prominence.

Military organizations did not shun new technologies; they embraced them. But very few officers had the time, or perhaps the inclination, to mull over their broader implications for the conduct of war. Ironically, this becomes clearest in the works of the great naval theorist of the age, the American Alfred Thayer Mahan. His vast corpus of work on naval history and contemporary naval affairs shaped the understanding of sea power not only in his own country but in others too, including Britain and Germany. Mahan made a powerful case that a dominant naval power, through its exercise of command of the sea, can subjugate the rest. In this respect, he argued, sea power was very different from land power: there was a vast difference between first- and second-rank sea powers but little difference between such land powers. Yet, although Mahan’s doctrines found favour among leaders busily constructing navies of steam-propelled ships, all of his work rested on the experience of navies driven by sail. His theory, resting as it did on the technology of a previous era, underplayed the new and unprecedented threats posed by mines, torpedoes, and submarines. There were other naval theorists, to be sure, including the Englishman Julian Corbett, who took a different approach, emphasizing the contingent nature of maritime supremacy and the value of joint operations. However, only the group of French theorists known collectively as the Jeune École (“Young School”) looked on the new naval technologies as anything other than modern tools to be fit into frameworks established in bygone times.

Strategy in the age of total war

Australia and New Zealand Army Corps troopsAustralia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) troops setting up camps on the Gallipoli Peninsula during World War I.(more)

Observe English schoolchildren practicing using gas masks in case of a chemical attack amid World War IIThe gas mask became a part of modern warfare with the introduction of chemical weapons in World War I. With the growth of total warfare and the targeting of civilians by air forces during World War II, the gas mask became a familiar part of daily life during wartime. In this video, English schoolchildren practice putting on and breathing through gas masks.(more)

See all videos for this article

It was during World War I that technological forces yielded a crisis in the conduct of strategy and strategic thought. Mass mobilization and technologies that had outpaced the abilities of organizations to absorb them culminated in slaughter and deadlock on European battlefields. How was it possible to make war still serve political ends? For the most part, the contestants fell back on a grim contest of endurance, hoping that attrition—a modern term for slaughter—would simply cause the opponents’ collapse and a victory by diktat. Only the British attempted large-scale maneuvers: by launching campaigns in several peripheral theatres, including the Middle East, Greece, and most notably Turkey. These all failed, although the last—a naval attack and then two amphibious assaults on the Gallipoli Peninsula (see Gallipoli Campaign)—had moments of promise. These reflected, at any rate, a strategic concept other than attrition: the elimination of the opposing coalition’s weakest member. In the end, though, the war hinged on the main contest on the Western Front. It was there, in the fall of 1918, that the struggle was decided by the collapse of German forces after two brilliant but costly German offensives in the spring and summer of that year, followed by a remorseless set of Allied counterattacks.